Faith Lost Is Culture Lost: Christopher Dawson’s Prophetic Warning

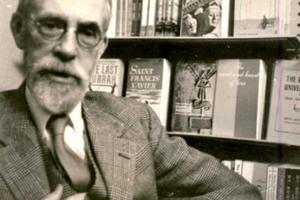

COMMENTARY: Why did Catholic historian Christopher Dawson fear a post-Christian world? His writings offer a sobering critique of modernity’s false gods.

British historian Christopher Dawson (1889-1970), while a guest professor of Catholic theology at Harvard, spent a week at Grailville in Loveland, Ohio — a cultural and retreat center near Cincinnati. The Grail movement, founded by a Dutch Jesuit and five laywomen in 1921, offered a residential program in Christian culture on Grailville’s 120-acre farm.

Those of us hosting Dawson in 1961 became acquainted with his writings, and, in between, recited the Divine Office, tended dairy and beef cattle, baked bread and harvested vegetables. Dawson, like others in Catholic Social Thought (CST), prioritized the rural and warned of the dangers of modern industrial societies. This irreconcilability of Christian culture with “modernity” was somewhat confusing to a mid-20th-century student raised in a predominately Catholic urban enclave.

CST proposals, seemingly anti-trade, continue to perplex, but the time has come to ask, “Were the prophetic warnings of Dawson valid?” The current revival of Dawson’s thoughts in Catholic and traditionalist circles assists. Bradley Birzer’s 2007 book provides an excellent scholarly portrait of Dawson’s thought (Sanctifying the World, Christendom Press). Also, Adam Schwartz in The Third Spring (The Catholic University of America Press, 2005) successfully weaves Dawson’s anxiety about Church and society.

The Central Factor of Religion

For Dawson, religion was the central factor in both personal and cultural life. Religion offers a sense of discipline and order and an objective reality far transcending one’s private experience. Dawson saw religion not as repressive, but rather as the central social and historical factor of all civilizations, including the pre-Christian.

A Christian humanist, according to Dawson, must understand the continuity of the Judeo-Christian culture with the Greco-Roman. He should be able to identify the Platonism of the Latin and Greek Fathers of the Church as well as the Aristotelianism of Aquinas and the scholastics. For Dawson, orthodox Christian truth, inextricably bonding spirit and matter, supplied a key to understanding all historical periods and cultural achievements. He also believed that Catholic Christianity was the basis of Western culture.

Dawson wrote, however, that as Western society became post-Christian, it would pervert the religious impulse, reducing it to subjective feeling, ritual without authority and tradition, and activity merely assumed to be moral.

Would Dawson have acknowledged the economic and life-extending achievements resulting from the adoption of classical liberalism? He probably would have because he admitted that rigorous study of underlying structures and statistics is a prerequisite for acceptable scholarship. Yet his fundamental perspective was anti-materialistic, and he lamented the degree to which 18th-century Liberalism and 19th-century Modernism advanced a post-Christian society.

Anti-Trade Bias

Dawson was concerned with the balance between the temporal and the transcendental, and he defined a Modernist as one who feels that there are no eternal truths and no divine law other than the law of change. The Modernist belief in linear progress, Dawson also feared, was consistent with socialism’s belief in human perfectibility, an attempt to create perfection on earth.

Dawson’s criticism of Modernism extends back to the humanism of the Renaissance, which rejected dependence on the supernatural, separated religion from reason, and created an independent rational sphere. This exclusive focus on humanity ultimately, if unintentionally, fueled secularization. Divinizing human nature and reason destroyed a unifying religious basis for social life and civilization. Although Dawson believed that modern science originated before the Enlightenment, he judged the Enlightenment as religious in origin but resulted in an orthodoxy of science and reason. Hence, we were spared neither from the narrow rationalism of 18th-century Classicism nor the emotional debauches of 19th-century Romanticism.

Dawson’s anti-trade bias relates to his perception of what is generally referred to as the 18th-century Scottish Enlightenment or Classical Liberalism. Dawson argued that this philosophy resulted in the unprecedented ascendancy of confident agnosticism. Furthermore, liberal capitalists did nothing to promote virtue or a good way to live. Dawson also maintained that liberalism was hollow because its apparent neutrality concerning virtue encouraged avarice. Dawson suggests that though liberals promoted various humanitarian reforms, they unwittingly sanctioned some evil. He concluded that by the early 20th century, the goal of the Liberal Enlightenment had been reached and Europe at last possessed a completely secularized culture. What remained were ideologies promoting false religions and pursuing propaganda as an attempt to conform minds into a mush that embraced neither imagination nor reason.

Material activities like economics, customs and laws, according to Dawson, could be practiced properly only under the aegis of a spiritual and moral order. Dawson found this harmony to be absent from modern, post-Christian society; hence, a society that has lost its religion becomes sooner or later a society that has lost its culture. Democracy, nationalism, liberalism, socialism, humanitarianism and progress were all secular surrogates and imbalanced substitutes for Christianity. And, Dawson warned, the virtues lauded in these substitutes would decay into some type of totalitarian secularism, like communism or fascism.

Was Dawson Prescient?

In his time, Dawson was seen as exhibiting a prophetic role; sufficient time has passed to appraise the value of his warnings.

Dawson feared that the machine world of capitalism and communism would do everything possible to mechanize all men, destroying the individual human person as unique. He assessed the development of nominally liberal states in the Anglo-Saxon tradition that were neither fascist nor communist. Such modern states would develop, wrote Dawson in 1936, into cradle-to-grave welfare states with school replacing the Church. Although these states would not attack religious institutions outright, they would be unwilling to tolerate any division based on spiritual allegiance. The dynamism in Western culture that came from Christianity would degrade into a form of post-Christian imperialism.

Dawson charged that academic overspecialization and capitulations to scientism hindered interdisciplinary analysis emphasizing literature and religion. Without a solid foundation of common principles based on natural law, those responsible for formulating the United Nations, for example, would attempt to create a sort of international contract based entirely on positivist and utilitarian principles giving lip service to humanitarianism. This could lead to a mere contest of power based on political realism.

Likewise, an education dismissive of natural law, Dawson feared, would end in dystopia. The utilitarian vision of education presents a materialist approach thinking only in terms of statistics with history reduced to chronicling events. This is in opposition to the old hierarchy of divinity, humanity and natural science. Twentieth-century education, he wrote, would shun excellence and create individuals who perceive themselves as the highest beings in the universe.

Dawson lived to see many of his worst predictions realized. However, while being a prophet of the extreme dysfunction of a post-Christian society, he exercised an essential function in insisting on culture’s natural religious yearnings.

He also made attempts to redirect society in a positive direction by advocating programs for the study of Christian culture. Christian culture, he suggested, could curb the social disunity that emerged with the more extreme elements of secular humanism. The Church was an especially compelling alternative to irreligious materialism because it neither neglects nor idolizes the tangible.

Dawson avoided abstract generalizations and maintained that a true science of human cultures requires anthropological research. He advocated a close study of natural rights as well as intermediary institutions. Dawson suggests that a distinctive culture can be formed and preserved even amid material ruin. As such, Catholics must confront modern unbelief directly and not fight defensively in a purely conservative spirit. Thus, he would probably tolerate coffee and doughnuts in a church meeting room surrounded by parking lots, rather than insist on a Christendom consistent with walkable churches and temples surrounded by farm-to-table bakeries.

In a letter to professor Bruno Schlesinger, who established a program of Christian culture at St. Mary’s College, Dawson wrote that as long as the Church is alive, Christian culture is alive. However, if a revival of Christian culture is required to confront social disunity and secular humanism, we must ask what comes first.

Do we pursue an environment conducive to Christian life? Or do we work on restoring faith out of which a culture evolves organically? Catholics, it would seem, should and will try to do both. However, prioritizing the restoration of faith may be the better choice.

Maryann O. Keating holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Notre Dame and is a member of the Indiana Policy Review Foundation. She frequently co-authors with her husband, Barry P. Keating, with whom she shares three adult children.

- Keywords:

- christopher dawson

- faith in the public square